Ah yes,

it is the winter wild

when a young man’s heart

naturally turns to thoughts of. . .

boatbuilding. |

|

Well, the poet didn't say it just like that, but then I'm not

a young man and don't want to be, either. So I have been thinking

of this winter season and boats. Of course, I've been known to

think of fruit cocktail and boats, so this is not unusual. Except

that the winter is the perfect time to fire up the garage heater,

spread out boat plans, and dream of a spring breeze beneath a

blue sky.

If you want to hum Irving Berlin's Blue Skies

while you're in the garage with the radio loud enough to irritate

your kids, go right ahead.

Those of you Duckmeisters who have read my columns know I love

little boats. So I've been looking at the Michalak Slam

Dink. For all of Jim's interest in practical

boats, he went off on curving rocker and sides here. It's probably

too short for my 240 pounds of dinner muscle, but it's a perfect

kid's boat with a big-boat bow and nice curves everywhere.

However, at 7 1/2 feet waterline it has the trouble most V-bow

boats have when the waterline is shorter than 10 feet. Bending

the chine could launch you through the garage window. I think

I'd want some extra chines around.

But there are several things you can do.

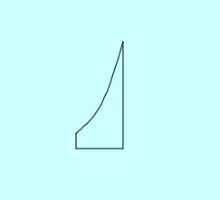

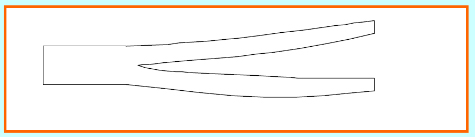

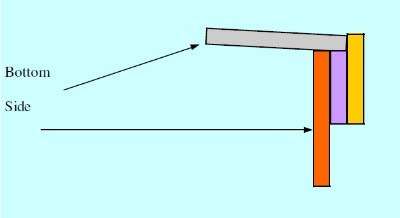

One is to put the chine on the inside and shape it like this:

| You can carve a little more out of the middle

than I have shown here. The top can be thicker, but not much,

since it is where the bend must take place the most. |

|

If you put the chine on the outside, you can use an ordinary

clothes iron to steam the chine while you bend it a little at

a time. I would not bend it too much at one time, since any bending

of wood beyond its' normal state weakens it. You might take a

tip from the Splendid Splinter, Ted Williams. Use a glass coke

bottle to rub the fibers smooth so they lay down as the chine

cools from the steam.

Now you're thinking of stitch and glue. Well, builders have come

up with different ways to keep the plywood together while the

glue sets. The original method-or the one I saw first- was by

Sam Devlin, wire ties. He may have begun with wires because he

was building boats with more stress on the ties than 8 to 10 footers.

Dynamite Payson then tried to make this idea easier by using

tape. He called it Tack and Tape, as he was temporarily nailing

the panels in place with frames, then taping the panels with strong

tape the full length of the panel. This enabled him to mix the

glue and filler right there in the chine. It also meant he didn't

have to cut wire ties off after the glue set.

Some builders found this method easy but not effective. By that

I mean the tape didn't make the panels as immovable as the wire

did. And the tape didn't work when the angle of the flare was

too great. A boat has to be designed with tape in mind, and this

can be done. Ken Simpson does this with his two and three part

boats.

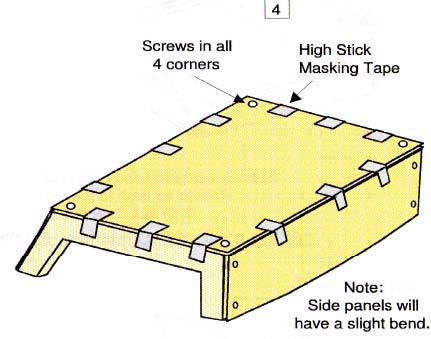

Ken specializes in take-apart boats which perform well. He uses

only slightly curved sides. This enables him to screw the corners

down and tape along the sides, as you see below. He uses Titebond

III to glue the insides first, while the tape holds the panels

in place. Ken recommends using the strongest tape you can find.

This is a page taken from Ken's design called Toter 2. It fits

in the trunk of most any vehicle, designed for paddles, oars,

or small motor. His plans include very good photographs of the

Tape and Glue process.

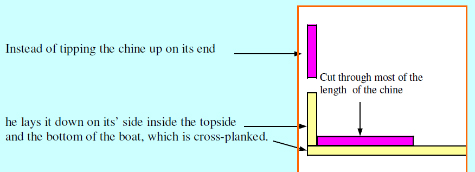

Another solution to the bend of small boats was described by

Harry Bryan in Wooden Boat Magazine a few years ago. His design

is called Daisy, a 11 foot dory skiff. He demonstrated an traditional

technique using the chine.

This is how he cuts it, not all the way along the chine. Glue

is applied to the inside of the cut after it is put in place.

One end will bend longer than the other, so the short end needs

to be long enough.

When I was cleaning out my tools closet, I found a box of clamps

sitting there. I stared at them long enough to imagine another

way of dealing with short boats with a curving chine. The idea

is to cut the sides out of, say, 3/8" plywood. Then cut a

strip one inch wide out of that same 3/8" plywood to lay

around the outside of the topside panel, clamped and glued. With

two edges you have 3/4" of landing width.

Then take the same clamps and clamp the

bottom to the outside layer of the chine. It's the same

method as the original Instant Boats only with plywood instead

of solid wood chines.

A traditional C clamp will not hold since it’s two

points are usually made movable. However I have about 30

spring clamps from Home Depot which will do the job. |

|

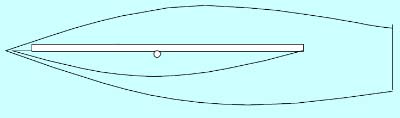

Now let's say you want to arc the bottom of the boat. This will

improve a small boat's rowing qualities, although it will not

necessarily sail any faster, except in light air. Still it's fun

to have some techniques at your disposal.

What you do is add a third layer of 3/8" strip, but make

it 1/2" taller than the other two chine layers. Then cut

the bottom slightly larger than the sides and press it in from

bow to stern. The bow width will have to be the same as the chine

width, with the bottom width increasing as you cut it aft.

Of course at this width, 9/8" you could also use screws

or nails for the side sections and then press the bottom section

in and glue it.

There is a variation on this plywood strips for

outside chines method, with an arched bottom. It’s easier,

but I’ve never actually done it. What you do is the same

two plywood chines on the outside, but the outside one is lower

than the other, creating the angle of arc.

With these two methods for an arched bottom, taping

the outside with glue would be best. You don’t necessarily

have to bevel the layers of plywood. In fact keeping the straight

edges inside the joint creates a way to trap the glue in place.

Just make sure the edges of the plywood

are sealed well.

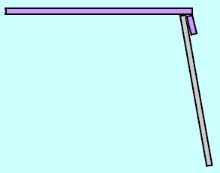

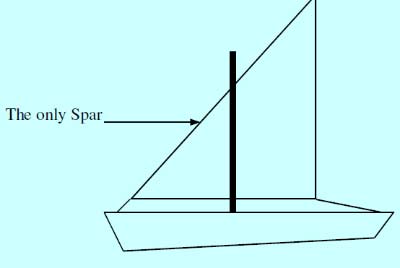

A great rig for a small boat is a lateen rig, along the lines

of the Sunfish and Sailfish. It can be built with a mast and two

spars which fit inside the boat, or a mast and one spar. It can

be built with no boom to go boom all over your head.

One advantage of a loose-footed sail is that the sail can be

cut fairly flat for windward work while it will still have a nice

curve for downwind sailing. The great limitation of a loose-footed

sail is it can only be sheeted in relation to the cut of the sail.

This usually means well aft. You have to deal with a loose-footed

sail, you can't just tie it off on a cleat and kick your feet

up. And it has another limitation, with which we can deal.

Sails pull based on the wind hitting the sail facing the wind,

and the lift of the sail's curve on the other side of the sail.

When the mast is on the windward side of the sail, it interferes

with the wind very little, but when the mast is on the other side

of the sail, that curve of the sail is interrupted. The sail becomes

flatter, which is not so bad, but with the loss of that leeward

curvature, the power of the sail is reduced. You won't lose performance

toward the wind, but on nearly all other points of sail you will.

So what can we do to get the sail on the other side of the mast,

when you tack? Lug sails have different methods, depending on

the size of the sail and the men on board. Since I'll assume you

are the only one in our small boat, we can leave the sail where

it is with little sail area before the mast or we can move the

sail.

In order to move the sail around the mast, the sail must be loose-footed,

which is good. The first option is to cut an equilateral triangle

sail. Then we hang it right at the midpoint along the top spar.

This actually doesn't look too bad to me.

This shape gives you some sail area higher than

the mast, where the wind is usually stronger than near the deck

and it gives you some sail area forward. In order to tack, this

is what we'll do. We'll have two lines fed through a hook in the

breastplate, one from the tack to the bow and another one from

the peak to the bow, on the windward side of the mast.

When you tack, pull the sheet attached to the peak-which goes

around the windward side of the mast-and the sail will rotate

around the mast behind it for the peak to now become the tack.

In fact, the wind will help the sail go around the mast but you'll

still need to tie it off.

The line in your hand, the sheet, will stay there,

it will simply turn over. You actually won't lose any momentum

tacking if you adjust your turn of the tiller to the movement

of the spar. Both lines from the spar will have to be run aft,

so you can tie them off without leaving your seat. I will give

you one warning: don't tack near the dock as the sail actually

never dumps its wind-Hello!

That's one way, and I've done it so I know it works.

There is another way, which I've never done or witnessed, but

I've deduced it from historical accounts and paintings of big

lateen rigs on fishing ships around the Mediterranean.

With this method the sail goes around forward of the

mast. Most everything else is the same as the previous method.

This method means the spar will have to be secured to the mast

very close to the mast top. The reason for this is so the spar

takes the wear of scraping the mast, rather than the sail. The

line which moves the sail around forward of the mast does not

come from the peak but the clew. It simply rotates the sail around

before the mast from the clew rather than rotating it around aft

of the mast from the peak.

The line from the tack to the bow does not move. An eyehook or

something similar is used so the line can rotate as the sail turns

over the mast. Each side will have two lines: one to pull the

sail around and one to tie it off.

This is a technique for a larger craft than, say, an 8-12 footer,

due to the need for room aft. The boat will have to be tacked

most of the way all around before the wind helps the sail. It

probably worked well enough on Mediterranean fishing boats which

would sail out on one tack, make their catch, turn around and

sail back home.

Paul Austin

***

|