Custom Search

|

|

| sails |

| plans |

| epoxy |

| rope/line |

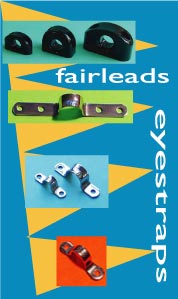

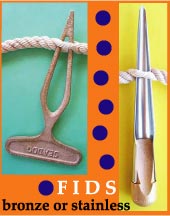

| hardware |

| canoe/Kayak |

| sailmaking |

| materials |

| models |

| media |

| tools |

| gear |

|

|

| join |

| home |

| indexes |

| classifieds |

| calendar |

| archives |

| about |

| links |

| Join Duckworks Get free newsletter Comment on articles CLICK HERE |

|

|

| Out There |

by Paul Austin - Dallas, Texas - USA Conrad's Ships |

|

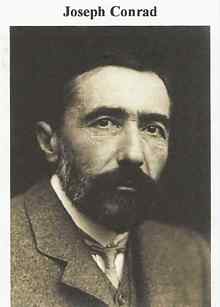

If there is a Shakespeare of the sea, it is Joseph Conrad. Born in Poland, he wrote stories and novels with nautical settings. Ten of his stories have been made into or inspired films. Living at the end of the British and French empires, he narrated the loss of meaning in the soul as men and women struggled with personal needs and public responsibilities.

He was born in a small town in Poland. Many of our greatest writers came from small towns or lower class circumstances. Conrad was among them. But why did he turn to the sea, living in Poland? When Joseph Conrad was a daydreaming boy in Cracow, he was already dreaming of the current Artic exploration. He often put down his classical studies, his mathematics and science to dream of ships on his bedroom wall. Great ships with brave captains at the wheel, holding course through huge breaking waves in a storm. Conrad's biographer John Stape says this:

But it takes more than imagination. It takes the fortune of destiny. Joseph Conrad's father had been a political rebel, his mother a woman of poor health. Both of them died by the time Conrad was 11 years old. Young Joseph was a restless boy, already taken away by adventure. So when he was 16 years old his grandmother allowed him to travel by train to Marseilles, to join a ship. Marseilles was an international port. The city displayed a slick blend of old grandeur and new debauchery. The tall elm-lined boulevards lay shadows across white bleached homes where many languages argued, bartered for flesh, and gambled fortunes in a moment. The cafe lights sparkled upon a blue ocean as yellow candles hid seductive eyes and soiled money. Conrad took it all in. He went to the opera, to the clubs, to the cafes. He saw Indian businessmen in turbans, disdainful Europeans on holiday, pick-pockets, insurance swindlers, and sea captains from exotic lands. In Marseille he knew the relative of a ship owner, who got him special passage on the creaky old barque, the Mont-Blanc. The destination was the French Antilles in the Caribbean. After passage through a storm in Majorca, the Mont-Blanc made its' destination, as Conrad later put it, with 'stagnation and poverty.' But for months at sea, Conrad saw the seafaring life. He saw the sailing routines, the handling of sails, swabbing decks, the call of morning bells, the relentless surrounding sea day after day until the port loomed ahead. When the Mont-Blanc set sail back for Marseille, he was on board. It was his last sea voyage as a passenger for years. After the Mont-Blanc arrived at Marseilles, she stayed only a month before embarking for Martinique. Now Joe Conrad was aboard as an apprentice, sleeping in the forward hold. The Mont-Blanc sailed through the Caribbean, then returned to France. After a 6-months stay in Marseille, Conrad shipped on the Saint-Antione. This barque sailed through the Caribbean also, returning to Marseille. Conrad was already gathering materials for his short stories which would come soon enough. Then he made one of his decisions for change. He shipped on a British steamer, Mavis, bound for Constantinople. Here the Polish Conrad had the opportunity to learn English. After a stay in Constantinople, the Mavis steamed for England, and Dover. England would be Conrad's home, though he didn't know it at the time. While he was in England, he signed on as a hand on the schooner Skimmer of the Sea, a family business sailing between English ports. He polished his command of English, learning navigation and seamanship. But compared to Marseille, Liverpool was boring where the Skimmer stopped, so he signed on with the British Merchant Marine, on board the Duke of Sutherland, bound for Sydney, Australia.

After a year's voyage, Conrad was back in London to sign on the steamer, Europa. This ship went to Italy, Greece and back to Sicily. After Conrad passed his Second Mate examination, he signed on the Palestine, a ship destined for tragedy. A fire erupted in the coal room, the ship burned and sank, with Conrad and the crew escaping in open boats on the east coast of Sumatra. He then sailed back to England on board the Sissie, as a passenger. In June 1884 Conrad was sailing on board the Narcissus, from South Africa to England. This voyage and ship gave him material for one of his classic novels, The Nigger of the Narcissus. (The title has caused trouble for Conrad since it's publication. The great majority of scholars view Conrad was exposing the injustice toward certain ethnic groups. This would be one of his major themes for the rest of his life. After all, he was always a foreigner to the British.) After returning, Conrad passed his First Mate's examination in December 1884. But he couldn't find a berth until April 1885, aboard the clipper Tilkhurst. This voyage took Conrad to Antwerp and then to the Black Sea, visiting ports he wrote about in The Mirror of the Sea. And then his life changed. The Industrial Revolution was slow to get to sea. But gradually, ships were being built of iron and steel, still with many wooden parts. Steam was coming. Now that ships were longer, they could carry more cargo, so the number of ships build declined. Conrad, with his newly earned First Mate's license, was being shoved out of a career on the sea. He was fortunate in being one of the last seamen to serve aboard the tall ships when they were profitable. He saw the last sights of tall rig sailing the crashing seas, seamen from many nations, strange captains and eerie vagrant sailors, exotic ports and massive cargos. He saw men who thought nothing of cruelty, fights, easy women (called the Sailor's Prerogative) and fortunes tossed up in a moment. When the Tilkhurst returned to England, Conrad decided to take the examination for the Master's license. He passed, thinking that 'I had vindicated myself from what had been cried upon as a stupid obstinacy or a fantastic caprice.' But the day of a man standing in the shadow of huge square sails was fading. After a brief stay in England, Conrad shipped on the Highland Village, for Java. It would lead to a year of the most exotic of his adventures. The Village was in Amsterdam. Conrad signed on as first mate, in charge of the stowage of the ship's volume of cargo. The task was formidable. In spite of the careful job he and his men did, the cargo made the Village roll at sea; a spar fell on him. He wrote in Lord Jim of 'many days stretched on his back, dazed, battered, hopeless and tormented as if at the bottom of an abyss of unrest.' He recovered and left for Singapore. There he saw the Javanese, Chinese an Malayan people of Singapore, mingling and blending their own cultures to form a wild, sparkling, dancing way of life. Nights were secretive, scented with drugs Conrad had never seen, private doors, strange rituals and serpentine tattoos. All of this Far Eastern culture took hold of his imagination. Never one to stay put, Conrad shipped on the Vidar, a ship suspected by the Dutch of being a slave runner. The Vidar went to Sumatra, Borneo, and the River Celebes. In Berau Conrad met Karl Olmeijer, a soldier of fortune with many children, dreaming wide dreams and hoping to escape the heat and oppression of the tropics. They spoke for many hours about fate, humankind's destiny and the character of men.

Conrad was in Bangkok when the captain of the huge bark Otago - 367 tons - died. He took the command. As captain he sailed her to Singapore and then to Sydney. At the helm he had to fight rough winds, sickness on board, and a union fight among the steamship workers. He stayed in Australia until boredom excruciated him. When he arrived back in England, he decided to write in English, beginning with his fist work of genius, Almayer's Folly. But a dockworker's strike forced him to look for work in Europe. There King Leopold of Belgium had owned the Congo since 1885. Leopold had put together a trading company, needing a deputy director who could speak French. Conrad was perfect for the job. One of the king's emissaries became the Marlowe of Heart of Darkness. When the captain of the river steamer Floride died suddenly, Conrad took over the job. Steaming down the Congo River was so oppressive Conrad's health never really regained the strength he'd had on the sea. In 1891 Conrad signed on as a first mate on the clipper Torrens. This great clipper sailed from Plymouth England to Adelaide, Australia. The Torrens was fast. Stape says it was the finest ship launched from the Deptford Yard. For 15 years no ship was as fast sailing from England to Australia. She once covered the 1600 mile trip in 64 days. Conrad wrote of her, 'a ship of brilliant qualities - the way the ship had of letting big seas slip under her did one's heart good to watch. It resembled so much an exhibition of intelligent grace and unerring skill that it could fascinate even the least seamanlike of our passengers.'

Much of the information here was found in Wikipedia and in the John Stape biography of Conrad, The Several Lives of Joseph Concard, Pantheon Books, 2007. There is a Conrad Society on the internet as well as copies of Conrad's original stories in Australian and New Zealand newspapers. CONRAD QUOTES: All a man can betray is his conscience. |