|

The Payson Butt Joint

- As shown with only the top completed, this joint replaces scarfs and butt blocks.

- One layer of 6 oz. biax per side for 1/4” plywood.

- Two layers of 6 oz. biax per side (or one layer of 12 oz, per side) for 3/8” plywood.

- Two layers of 12 oz. biax per side for ½”plywood.

- Biax tape used in structural applications, or if plywood will bend considerably.

- Regular ‘glass cloth can be substituted in lightly loaded areas.

- Biax should be 45/45 style weave.

- 6:1 slope ratio is fine for most joints. Increase on highly loaded joints or areas that receive considerable bend.

- Tapers and back cuts do not have to be precise, a rough rasp finish is perfect.

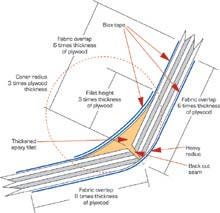

Structural Fillet Anatomy

- Fillet mix, 50/50 silica & milled fibers or wood flour (add silica to stiffen mixture).

- Fillet extends 3 times plywood thickness in each direction, from centerline of joint.

- Inside corner receives two layers of 12 ounce biax, inner layer overlaps 3 times plywood thickness, outer layer overlaps 6 times (see drawing).

- Outer corner, radiused 3 times plywood thickness.

- Outer corner receives 1 layer of 10 ounce biax with 6 times the plywood thickness overlap (plus sheathing if desired).

|

Fillet Types

There are three basic fillet types; heavy structural, light structural and cosmetic.

All fillets have a thickened epoxy mixture on the joint. The actual mix is dependent on the fillet type. Heavy structural fillets are 50/50 silica and milled glass fibers, light structural fillets have the same mixture with some wood flour or micro spheres (Q cells, micro balloons, etc.) added to ease sanding effort. Cosmetic fillets are mostly light materials, such as Q cells, for easy sanding, though silica may be added to control viscosity.

A heavy structural fillet has 2 layers of biax on the inside and at least one layer of biax on the exterior of the joint. These types of fillets are usually along the hull planking seams and other highly loaded areas, like centerboard cases, bulkheads and keels.

A light structural fillet is much like the heavy, except a single layer of biax is used on both sides of the joint. Regular cloth of similar weight, can be substituted for biax in most light structural fillets, but only on the outside of the joint in most situations.

Cosmetic fillets are decorative in nature and don’t require fabric over them, though many will for abrasion resistance. Regular cloth is used, not biax.

Filler materials for a cosmetic fillet are selected for ease of sanding, sometimes color (natural finishes) and workability. Q cells, micro balloons, wood flour, etc., are all common materials. These types of fillets are just to round off inside corners to make cleaning easier, to shed water, hide seams, prevent trapped moisture, etc. If the fillet is to provide strength to anything, it will need silica, milled fibers or other “fibrous” material added to improve strength.

As shown above, it’s often wise to “back cut” the pieces to be filleted. This allows the end grain to be covered in epoxy, protecting it. This doesn’t have to be neat, I use a big grinder or belt sander to whack off the edges on these back cuts. So long as the panel alignment is good, the edges (gaps) can be off by a 1/2”. Epoxy fills these gaps easily and makes the joint stronger too.

Tape overlap and height of the fillet are minimums. Other then extra epoxy, there is no problem with additional materials.

As a rule, you don't need to be particularly precise about these joints. The keys to remember are to back cut the contact area, so the goo can get in and around the end grain and of course the appropriate heights for the fillets and fabric schedule (if required) applied over them. The inside corner of a joint is the most important, in terms of strength and stiffness, but this doesn't mean forget about the outside. What this means is you can use the hull sheathing, to supply the fabric overlay on a chine for example, because this is an outside corner. On heavy structural fillets, the inside will always need fabric, with plenty of stagger and overlap. Back to neatness of the raw wood elements, you can hack it out with an ax, so long as alignment is where you want. The epoxy will fill, seal and bond the most butchered of joints, which under paint is invisible. Naturally, if you are looking to create a varnish finish, this isn't a good looking joint, so a mechanical scarf or butt block would be more desirable.

Disclaimer: light weight/small boats, such as canoes and kayaks can get by with smaller fillet dimensions. These types of boats just aren't "loaded" sufficiently enough to need the "3:1" rule employed. In fact, many cases (light boats) can skip the fabric reinforcement, according to my (and others) testing. Simply put, some 1/4" plywood joints, bonded with a 2:1 fillet (as an example), will typically still fail in the wood, not the glue line, in spite of the lack of fabric, which is good enough for me. Assuming good application and wetout techniques are used.

|